Both horses and riders can carry a lot of fear that blocks the joy they could be having together. Traumatic experiences can set everyone back and rightfully so. We all go into protective mode when something bad happens. Sometimes we lose confidence, in our bodies, in the world around us, and in our horses.

When I was teaching a lot of liberty work clinics, many of the people who attended had either been bullied into being pushy with their horses by trainers, or they had gotten hurt by horses. When either of those or both of those things happen, a natural reaction is to draw into oneself and find something else to do; perhaps some other way to be with horses that’s not so stressful, or put them in the pasture and leave them, saying that horses don’t need to be ridden, they’re totally happy having minimal interaction with humans. That’s all fine and true to some extent, but there is so much that is not being addressed here. It may allow the person to remain in their comfort zone or create an even narrower one, in order to accommodate their fears. And the fact they can provide a pasture and freedom is huge and wonderful! But it doesn’t develop the relationship with the horse, and it doesn’t develop the part of themselves that can really listen to the horse. Bottom line – it is all fear-based, as is bullying types of training.

While working with horses, I must be conscious of so much around me, like on every plane and in every dimension. Even with all that consciousness, something may enter my zone or my horse’s zone and upset the apple cart.

We all know that – you have your horse “de-sensitized” to large trucks, bicycles, etc. but what about that odd machine that comes down the railroad tracks that makes a strange noise? Or the new silent electric bikes that make some noise that bothers some horses? The horse may be fine with some stimuli but really worried about others.

If you stay in the arena, you may not need to experience any of these things. But horses react to things happening in or around arenas too.

A cumulative event that happens to horses and humans is trigger stacking. One bad accident occurs, or one trainer mistreats the horse, but then another insult occurs. The frightened horse falls into a ditch on the trail. The frightened horse is forced to do something he’s terrified of, and it goes on like this, until he has a build up of tension under the hood so he becomes reactive to many more things than what started it. Horses who have endured repeated trauma may freeze, shut down or explode, the same responses that humans experience when they are the victims of repeated trauma. They may do a combination of these things. Horses may seem “bomb-proof” to some people because they’re shut down, but if you take them out of whatever ”comfort zone” they have, they may explode. This is because they are living in their sympathetic nervous system, their “flight/fright/freeze” mode. We want to embody treatment and exercises that bring the horse into the parasympathetic nervous system, the “rest and relaxation” mode.

A cumulative event that happens to horses and humans is trigger stacking. One bad accident occurs, or one trainer mistreats the horse, but then another insult occurs. The frightened horse falls into a ditch on the trail. The frightened horse is forced to do something he’s terrified of, and it goes on like this, until he has a build up of tension under the hood so he becomes reactive to many more things than what started it. Horses who have endured repeated trauma may freeze, shut down or explode, the same responses that humans experience when they are the victims of repeated trauma. They may do a combination of these things. Horses may seem “bomb-proof” to some people because they’re shut down, but if you take them out of whatever ”comfort zone” they have, they may explode. This is because they are living in their sympathetic nervous system, their “flight/fright/freeze” mode. We want to embody treatment and exercises that bring the horse into the parasympathetic nervous system, the “rest and relaxation” mode.

I work with a gelding who has had some rough handling in his early years, and then spent years with relatively no training, rand highly reactive to noise, vibration, sudden movements: you name it. A lot had to change for him, which it did, in the form of a wonderful, quiet new owner and some slow, considerate training. We’re still working to defuse those stressful responses because, while he has worked through a lot, he was a victim of trigger stacking in his early years.

Bodywork – Bodywork was not always something this boy could tolerate, so it was done from a distance until I could get close, and until he got his special person. Fortunately, she was studying to become a bodyworker, which helped him immensely.

Bodywork – Bodywork was not always something this boy could tolerate, so it was done from a distance until I could get close, and until he got his special person. Fortunately, she was studying to become a bodyworker, which helped him immensely.

Liberty exercise and ground exercise – These activities have helped this horse’s state of mind immensely, before riding and even now, while he is a riding horse. A horse started with a frayed sense of worth needs this quiet building to bring him back to himself, to feel proud of himself. Horses can be happy with this form of interaction and so can people, because there is such rich communication available.

Riding – If the horse in question is able to be ridden, the process may be slow, but it should always be rewarding for the horse and human. Not pushing, rushing, or otherwise expecting something he isn’t able to give yet. At the same time, it’s still essential in all the work to create boundaries; no pulling or stepping on you, etc.

As there is so much cruel, hurried training or lack of training in the world of horses, more horses are coming to us with more trauma. A common method of training and part of some de-sensitizing, especially for non-compliant individuals, is to flood the horse’s space with scary objects, behaviors, sudden movements, which can completely overload the nervous system. Horses who twitch a lot or shy at a lot of things may have had this beginning. These horses need to be restarted in a quiet way, without the flooding or harsh treatment, and slow introduction to new things. It’s helpful to see what the new start exposes in terms of behaviors and fears.

Nearly every horse I work with currently has some level of trauma, or has worked through a lump of it. My rescue mare came to me some years ago carrying a lot of trauma, that was lodged in various cells in her body. She was enjoying her groundwork training and the people who were kind to her at the time, but there was an emotional sludge stuck here and there.

Once I could work with her each day, we could unravel it more effectively. I have worked with other horses who have had worse emotional sludge, and depending upon the facility of the owners, bodyworkers and trainers, they have been able to release it. I use a combination of bodywork and ground exercises to bring this about. Trauma is always part of the body, but the healing takes place only when we are able to stop reacting to it. I say reacting, because we will always respond, but it doesn’t have to be reaction. For most, it’s a series of gentle shifts, for some, it takes a lifetime. While we worked, the various triggers emerged and subsided and were no longer something she had to fixate on. As she goes through life, she will not be reactive unless provoked, she will remain calm and curious in her surroundings – as long as she has proper support.

And what does that support look like? Perhaps the most important thing that must be nurtured is mutual trust. When the horse sees her person as someone she can trust, then the nervous system can move from the high anxiety sympathetic nervous system into what we call the parasympathetic mode.

How do we develop this trust?

One way is to always be a protector to your horse. When you have your horse’s back, then your horse will have yours. He knows he can trust you.

I believe horses know what we’re saying, perhaps not the words themselves, but the intention behind them. Some people have horses all their lives and never know how to build trust with them, as long as they can ride and get where they want to go. I consider that to be a major disconnect, a disservice to the animal, and a joy the owner is missing out on.

For those who are starting out with horses, the problem is often the same, as so many riding establishments have a disconnected view. Students learn the disconnect and feel guilty for having sensitive feelings about horses, for becoming fearful because they can’t feel safe, for not having the opportunity to develop trust as well as necessary boundaries.

I assess how well horse and human are doing with this by

- Checking in with dimensions – our front/back, side/side, up/down dimensions.

- How well does the horse recover from a scary event, i.e., a plastic tarp blowing, a fall, trailer accident? How well does the person recover, i.e., continue to recount the scary incident, unable to move forward, etc.? Some things take longer than others to recover from.

- How well does the horse embrace gentle work, i.e. bodywork, groundwork?

So we come full circle to the fear that began this article – a fear that has every right to be there, but that doesn’t have to stay and burrow down and remain the basis for the way people interact with horses. Like everything good in life, it takes the time it takes to build the trust, unplug the trigger stacking and subsequent reactions, and move everybody involved to authentic, thoughtful responses and safety.

years, I bought horses that could do what I was doing, endurance riding, though the first one was chosen because I just fell in love with her. I knew her and had been riding her for a year. Then we got into endurance riding. Even though she wasn’t the most desirable candidate for that sport (she tripped) she completed almost 800 competition miles with me. I went looking for endurance prospects after that, and I fell in love with them too. Which means, it’s possible to fall in love with a horse that can partner with you in what you enjoy doing.

years, I bought horses that could do what I was doing, endurance riding, though the first one was chosen because I just fell in love with her. I knew her and had been riding her for a year. Then we got into endurance riding. Even though she wasn’t the most desirable candidate for that sport (she tripped) she completed almost 800 competition miles with me. I went looking for endurance prospects after that, and I fell in love with them too. Which means, it’s possible to fall in love with a horse that can partner with you in what you enjoy doing. that may come up in your new journey.

that may come up in your new journey. Horse health is such a broad topic, it cannot be limited to what we do in terms of providing hands-on bodywork, or diet or exercise. It also includes emotional, psychological and psychic health, activities to create communication and increase curiosity and the way we ride.

Horse health is such a broad topic, it cannot be limited to what we do in terms of providing hands-on bodywork, or diet or exercise. It also includes emotional, psychological and psychic health, activities to create communication and increase curiosity and the way we ride. In February, I conducted a Q&A session where one of the questions was about a horse who had stopped eating, and discussing what to do to get the horse eating again. The practitioner with the issue said the horse had just lost his owner and regular stablemates due to death. He had been moved to a new barn with new horses and people.

In February, I conducted a Q&A session where one of the questions was about a horse who had stopped eating, and discussing what to do to get the horse eating again. The practitioner with the issue said the horse had just lost his owner and regular stablemates due to death. He had been moved to a new barn with new horses and people. The horse needed a bridge to his new life, where there are very good things available. He just can’t reach for them right now. A horse in this state can go unnoticed in traditional circumstances where people will focus on the lack of appetite but not think about or know how to address the grief.

The horse needed a bridge to his new life, where there are very good things available. He just can’t reach for them right now. A horse in this state can go unnoticed in traditional circumstances where people will focus on the lack of appetite but not think about or know how to address the grief. shun connection, though bodywork, a simple laying on of hands, could be very helpful and give valuable information too. Grief makes the body tight and dry, flaky, unresponsive. To loosen up those areas – particularly around the heart – would help the horse feel better in himself, and lo and behold, he may eat.

shun connection, though bodywork, a simple laying on of hands, could be very helpful and give valuable information too. Grief makes the body tight and dry, flaky, unresponsive. To loosen up those areas – particularly around the heart – would help the horse feel better in himself, and lo and behold, he may eat. more devastating.

more devastating. Make sure the horse has companions. Not all horses grieve the same way. Some are sad but they are more able to go through their days as they have a more developed understanding of their stablemate or owners’ passing. That understanding can be supportive to the grieving horse.

Make sure the horse has companions. Not all horses grieve the same way. Some are sad but they are more able to go through their days as they have a more developed understanding of their stablemate or owners’ passing. That understanding can be supportive to the grieving horse. It’s very common for horses to be afraid of bodywork, especially if they have received fear-based training or a number of unpleasant veterinary procedures. Of course, veterinary procedures and surgeries are often non-negotiable. When I have a procedure personally, I can only imagine what that feels like to the horse who doesn’t understand why it’s being done to him or her.

It’s very common for horses to be afraid of bodywork, especially if they have received fear-based training or a number of unpleasant veterinary procedures. Of course, veterinary procedures and surgeries are often non-negotiable. When I have a procedure personally, I can only imagine what that feels like to the horse who doesn’t understand why it’s being done to him or her.

If your horse is continually miserable or reactive during a visit from any practitioner, it may be worthwhile to re-evaluate that professional relationship.

If your horse is continually miserable or reactive during a visit from any practitioner, it may be worthwhile to re-evaluate that professional relationship. Sometimes I find that the owner isn’t aware of what other professionals are doing with their horses.

Sometimes I find that the owner isn’t aware of what other professionals are doing with their horses.

Years ago, when I was riding endurance, many rider/horse teams would head to El Paso during the winter months to ride. Horses had not had much riding time in the colder climates so one had to be careful as they traveled in the deep desert sand. Often the injuries that went unnoticed from the winter riding would appear in the spring.

Years ago, when I was riding endurance, many rider/horse teams would head to El Paso during the winter months to ride. Horses had not had much riding time in the colder climates so one had to be careful as they traveled in the deep desert sand. Often the injuries that went unnoticed from the winter riding would appear in the spring.

ve around freely is different than the measured, focused exercise we ask of a horse in daily work. Both are very important.

ve around freely is different than the measured, focused exercise we ask of a horse in daily work. Both are very important. Walking on different types of terrain for horses who can manage it is vital.

Walking on different types of terrain for horses who can manage it is vital. comfortable being ridden anymore. He’s now 26. He enjoys walks and arena activities. He is also teaching our young mare Red to be more curious than she already is. I think this is an excellent way for him to spend his golden years.

comfortable being ridden anymore. He’s now 26. He enjoys walks and arena activities. He is also teaching our young mare Red to be more curious than she already is. I think this is an excellent way for him to spend his golden years.

Generally, back pain affects the entire body. If you have ever experienced back pain, it can have a debilitating affect on your activity, from walking to sitting, standing and even lying down. If someone wants to make you do exercises if you’re in excruciating pain, that can be the worst thing for you.

Generally, back pain affects the entire body. If you have ever experienced back pain, it can have a debilitating affect on your activity, from walking to sitting, standing and even lying down. If someone wants to make you do exercises if you’re in excruciating pain, that can be the worst thing for you.

Red isn’t a replacement, she is her own horse. She is young and curious about everything, and especially her interactions with humans and her training. She loves her training. What I’m seeing in her is that everything is an adventure. While her first years were fraught with uncertainty, fear and mistreatment, when she didn’t want anyone to catch or touch her, she has now landed somewhere where everyone listens to her and she wants to listen.

Red isn’t a replacement, she is her own horse. She is young and curious about everything, and especially her interactions with humans and her training. She loves her training. What I’m seeing in her is that everything is an adventure. While her first years were fraught with uncertainty, fear and mistreatment, when she didn’t want anyone to catch or touch her, she has now landed somewhere where everyone listens to her and she wants to listen.

These are horses who have no relationship with their riders. They are ridden by many different riders in preparation for this event and considered “schoolmasters.” But to go through an event at this high level of stress, they need the relationship. When things get scary it’s not enough to simply know how to ride, you need to know the way that animal thinks, moves, it’s preferences, what frightens it, know it deep down so that you can set up the best possible outcome. If introducing a horse to new things, it’s best if he has a familiar, much loved person to help him or her through it all.

These are horses who have no relationship with their riders. They are ridden by many different riders in preparation for this event and considered “schoolmasters.” But to go through an event at this high level of stress, they need the relationship. When things get scary it’s not enough to simply know how to ride, you need to know the way that animal thinks, moves, it’s preferences, what frightens it, know it deep down so that you can set up the best possible outcome. If introducing a horse to new things, it’s best if he has a familiar, much loved person to help him or her through it all. addle, not a short stint in an Olympic arena that involves maybe 5-10 minutes of connection! Plus the stress level is way down on the meter. We were riding to win a t-shirt, not an Olympic gold medal.

addle, not a short stint in an Olympic arena that involves maybe 5-10 minutes of connection! Plus the stress level is way down on the meter. We were riding to win a t-shirt, not an Olympic gold medal.

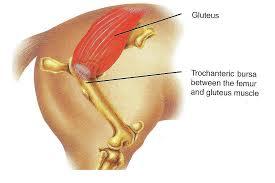

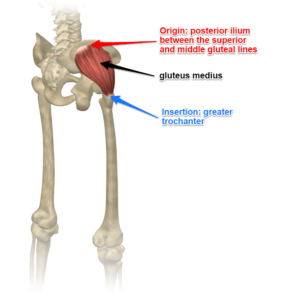

All of us – horse and human – hold tension in our bodies and we also have areas that just don’t speak. We have places that don’t work as well as others. My right leg can get funky in the hip socket, for example. I could sit up there and worry about what a terrible rider I am and I shouldn’t ride because I’m not always symmetrical and blah blah blah, but if I focus on all the dysfunction, then I am missing what my body can do, and how it can support the areas that aren’t working quite so well. My horse has stuff going on in her hips also. I focus on the healing available in her body. And guess what? Even though she has that stuff, she is a beautiful mover. I sit on her, and I feel each part of me and her, and focus on the parts that work really well while holding an awareness of what I’d like to have shift.

All of us – horse and human – hold tension in our bodies and we also have areas that just don’t speak. We have places that don’t work as well as others. My right leg can get funky in the hip socket, for example. I could sit up there and worry about what a terrible rider I am and I shouldn’t ride because I’m not always symmetrical and blah blah blah, but if I focus on all the dysfunction, then I am missing what my body can do, and how it can support the areas that aren’t working quite so well. My horse has stuff going on in her hips also. I focus on the healing available in her body. And guess what? Even though she has that stuff, she is a beautiful mover. I sit on her, and I feel each part of me and her, and focus on the parts that work really well while holding an awareness of what I’d like to have shift. With Ortho-Bionomy© for both horse and rider, we can learn what is holding up the bus. Riding instructors have wonderful ways of encouraging the horse forward, ways for riders’ to hold their legs so that the legs are not being counterproductive for the horse, or to sit correctly so as not to impede the horse’s movement – all of that has to do with the anatomy and the relationship of the two bodies working in sync, or not.

With Ortho-Bionomy© for both horse and rider, we can learn what is holding up the bus. Riding instructors have wonderful ways of encouraging the horse forward, ways for riders’ to hold their legs so that the legs are not being counterproductive for the horse, or to sit correctly so as not to impede the horse’s movement – all of that has to do with the anatomy and the relationship of the two bodies working in sync, or not.

Certainly, work can be done on some of these issues independently of the horse/rider relationship, and I do that in many cases where a person may need individual table work ahead of a horse/rider session, or the horse needs to receive an entire session on his own. If someone has major back trouble, I’m going to work on that, and same with the horse. But once the bodies are free of great inhibition, we can bring them together and see where they can strengthen and enhance each other, and bring space into the relationship that may have been restricted before.

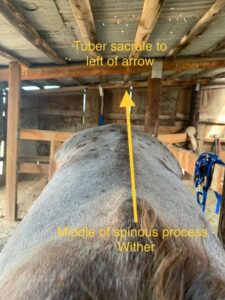

Certainly, work can be done on some of these issues independently of the horse/rider relationship, and I do that in many cases where a person may need individual table work ahead of a horse/rider session, or the horse needs to receive an entire session on his own. If someone has major back trouble, I’m going to work on that, and same with the horse. But once the bodies are free of great inhibition, we can bring them together and see where they can strengthen and enhance each other, and bring space into the relationship that may have been restricted before. ways of beginning this work. While grooming your horse you can feel along the spine for any irregularities. If you don’t know anatomy, it’s helpful to get a simple equine anatomy book – and a human one while you’re at it! Learn where the bones are. Everything else is related to or attached to the bones in some way, so it’s a great place to start.

ways of beginning this work. While grooming your horse you can feel along the spine for any irregularities. If you don’t know anatomy, it’s helpful to get a simple equine anatomy book – and a human one while you’re at it! Learn where the bones are. Everything else is related to or attached to the bones in some way, so it’s a great place to start.

After that I may do a little bit of bodywork on areas I see are not working so well on my horse, and stretch out myself. You can apply your own exercises, such as qi gong, yoga, Feldenkrais, etc. and in Ortho-Bionomy© we have a lot of self-care exercises for people and ones you can do for your horse. Some of them I have adapted to use in the saddle as well.

After that I may do a little bit of bodywork on areas I see are not working so well on my horse, and stretch out myself. You can apply your own exercises, such as qi gong, yoga, Feldenkrais, etc. and in Ortho-Bionomy© we have a lot of self-care exercises for people and ones you can do for your horse. Some of them I have adapted to use in the saddle as well. Much thought has been given over centuries to how to ride efficiently and so as to bring out the best in the horse and rider. With the Mounted Body Balance™ approach, an older horse can move better than he or she ever has and so can her rider. Life isn’t static so we can’t guarantee that any of us are not going to have some physical challenges, but there is a lot we can solve and make more comfortable with this type of work. A horse may be able to help you with your body issues without impairing his/her own stride or balance. Of course, aging will limit what you can do but why not try to do what you love comfortably for as long as you can? As a physical therapist friend of mine says, “I’m here to help you be able to do what you love for longer.”

Much thought has been given over centuries to how to ride efficiently and so as to bring out the best in the horse and rider. With the Mounted Body Balance™ approach, an older horse can move better than he or she ever has and so can her rider. Life isn’t static so we can’t guarantee that any of us are not going to have some physical challenges, but there is a lot we can solve and make more comfortable with this type of work. A horse may be able to help you with your body issues without impairing his/her own stride or balance. Of course, aging will limit what you can do but why not try to do what you love comfortably for as long as you can? As a physical therapist friend of mine says, “I’m here to help you be able to do what you love for longer.”