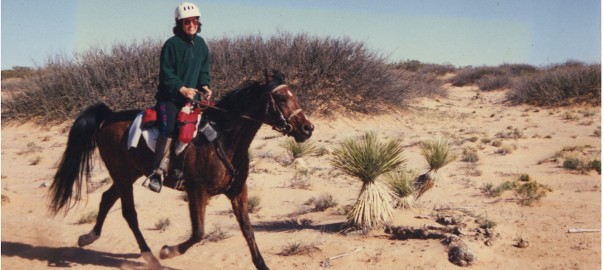

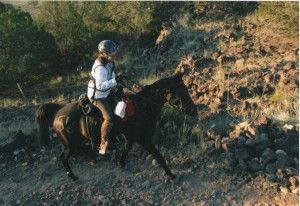

The trail followed the creekbed then crossed it, curving like a snake up the side of the canyon. My horse stopped to drink in the creek, then scaled the rocky side of the canyon and the switchbacks, a steep drop on one side, a canyon wall on the other.

My trust was wholly in this horse, who has carried me on so many trails, mountains, in canyons, badlands and deserts. We are in a part of the country where we have it all – and so we have practice d on it all. We have ridden through small cowtowns in Colorado, ghost towns, and remote landscapes that vehicles can’t get to, up to mountain peaks that required that I get off and walk. We come prepared, but we also know that anything can happen, and we are dependent upon one another. We know each other intimately, my horse knows my every shift in the saddle, lift of the rein, and I know how she will place her feet, what she fears and what doesn’t faze her. We support each other through each turn in the trail.

d on it all. We have ridden through small cowtowns in Colorado, ghost towns, and remote landscapes that vehicles can’t get to, up to mountain peaks that required that I get off and walk. We come prepared, but we also know that anything can happen, and we are dependent upon one another. We know each other intimately, my horse knows my every shift in the saddle, lift of the rein, and I know how she will place her feet, what she fears and what doesn’t faze her. We support each other through each turn in the trail.

People have for centuries, relied on the horse not just  as mode of transportation, but as a partner in daily life. The horse was part of the economy, and necessary, but bonds were formed, and the horse and rider would move through their days together as one.

as mode of transportation, but as a partner in daily life. The horse was part of the economy, and necessary, but bonds were formed, and the horse and rider would move through their days together as one.

I speak of this because the bond that we work at on the ground can pave the way for the bond we have in the saddle.

Recently someone wrote about how as children we formed bonds with horses while riding, when allowed to simply slip on their backs with perhaps only a halter and take off, or spend our days playing with them. I compared that to the drill of riding lessons, because I experienced both as a child. What began to happen for me was that although I wanted to learn to ride, I also wanted to spend time with the horse, just feeling the fur on his back, wrapping my arms around his neck, feel what it was like to be one with this deeply special animal.

The oneness came because I was small and happy and the thought of falling off or not knowing how to ride really didn’t enter my head. It was only w hen a very fierce riding instructor got frustrated with me and told my mother that I would never learn to ride properly, that I became heartbroken. My mother was angry and we stopped the riding lessons then, and found someone more gentle to teach me.

hen a very fierce riding instructor got frustrated with me and told my mother that I would never learn to ride properly, that I became heartbroken. My mother was angry and we stopped the riding lessons then, and found someone more gentle to teach me.

The joy that I felt around horses had nothing to do with what the instructor was talking about, I was certain. But because I was so fiercely devoted to horses, I learned to ride anyway, and I learned to ride in a way that riding instructor probably would be horrified by. I learned to ride endurance, and ride til the sun went down and the grime in my socks and on my face had reached legendary proportions. I wanted to do endurance because I wanted to camp with my horse, I wanted to be with my horse all day long, having adventures together, seeing new territory and sharing joys and fears. Shows and other events didn’t offer this. They offered a way to present accomplishments to the world. It was about cleaning up, performing in a short space of time, and putting the horse away. Endurance offered a way to ride without having to win in the way others won. “To finish is to win,” is the motto.

That suited me fine. It also suited me that if for some reason we couldn’t ride, I got sick or the horse was off, we could spend the day in camp together. I could read books and take walks and it was okay.

That suited me fine. It also suited me that if for some reason we couldn’t ride, I got sick or the horse was off, we could spend the day in camp together. I could read books and take walks and it was okay.

This was the avenue by which I came to liberty work, to deepen the relationship on the ground, based purely on my passion for horses and desire to connect as I had as a child, and as I had scaling rugged mountains with my horses. I am no longer a child, and there isn’t always a mountain to climb, and some horses are not designed to do that kind of task. So there has to be a way to work with them without those challenges, a simple, direct way that derives from their own language and desire to connect with us too.

This is where the Liberty Foundations come in. A simple language that can be learned, and continue to be learned by people, that the horse already knows. It can be done with one horse or many. It can lead to a dance or simply quiet joy. It can lead to fabulous performance or a simple trail ride.

This is where the Liberty Foundations come in. A simple language that can be learned, and continue to be learned by people, that the horse already knows. It can be done with one horse or many. It can lead to a dance or simply quiet joy. It can lead to fabulous performance or a simple trail ride.

It allows us to slow down and be in touch with our senses, our dimensions, those things that horses are very aware of every waking moment. They are part of survival, and for us to come back to this gives us better coping skills as well.

When I say my greatest teacher of horsemanship, including all the teachers I have had, is the horse, I mean it at the deepest level possible.

(c) Susan Smith, Horses at Liberty Foundation Training, Equine Body Balance (TM)

Please see my

Events for information on upcoming clinics and workshops.